In 1977, New York was a city on the brink. Facing total financial insolvency, the city had gutted its police and fire departments two years prior, firing some 50,000 city workers in the single largest lay-off in New York City history. The move had ushered in an era of what police labeled “misdemeanor homicides,” during which a guilty murder plea guaranteed no more than three years in prison (and sometimes landed criminals no jail time at all).

Unions organized a media campaign titled “Welcome to Fear City,” warning would-be tourists that “hotel robberies have become virtually uncontrollable,” “you should never ride the subway for any reason whatsoever,” and that all should “stay away from New York City if you possibly can.”

To make matters worse, a deranged serial killer operating under the alias “Son of Sam” was loose in the streets. He managed to kill six people and seriously injure seven more with a hunting rifle before his capture on August 10, 1977. In the words of a TIME magazine editorial of the day, “Scarcely anyone today needs to be told about how awful life is in nerve-jangling New York City, which resembles a mismanaged ant heap rather than a community fit for human habitation.” Demonized by journalists the world over, the city’s public image had never been so menacing.

Under the auspices of commissioner John Dyson and deputy commissioner Bill Doyle—both veterans of financial marketing—the cash-strapped New York Department of Commerce (DOC) bet the city’s future on a Hail Mary investment. It upped the state’s annual tourism budget from $400,000 to $4.3 million to fund the most audacious and far-reaching rebranding campaign the state had ever seen.

Dyson and Doyle’s thinking was chiefly pragmatic. As Miriam Greenberg, sociology professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz, explains in her book Branding New York, “Tourism marketing transcended conflict, presenting an inclusive face of New York City for everybody, rich and poor, citizen and visitor, to enjoy.”

The key was finding a way to capture and convey this unifying spirit. “I remember Bill Doyle saying that the words that matter in advertising are: ‘new,’ ‘free,’ ‘improved,’ and ‘love,’” recalled Dyson. “And he comes back the next day and says, ‘Well, ‘I love New York’ has ‘love’ and ‘new’ in it. So I got two of the four powerful words of advertising.’”

The city had its slogan—now it needed a visual. Enter Milton Glaser. Having made a name for himself as the co-founder of New York Magazineand the technicolor visionary behind the much-acclaimed poster for Bob Dylan’s 1967 “Greatest Hits” album, the Bronx native was an obvious choice given both his prodigious talents and lifelong connection to the city. “I never separated the city from myself,” Glaser told the New York Times. “I think I am the city. I am what the city is. This is my city, my life, my vision.”

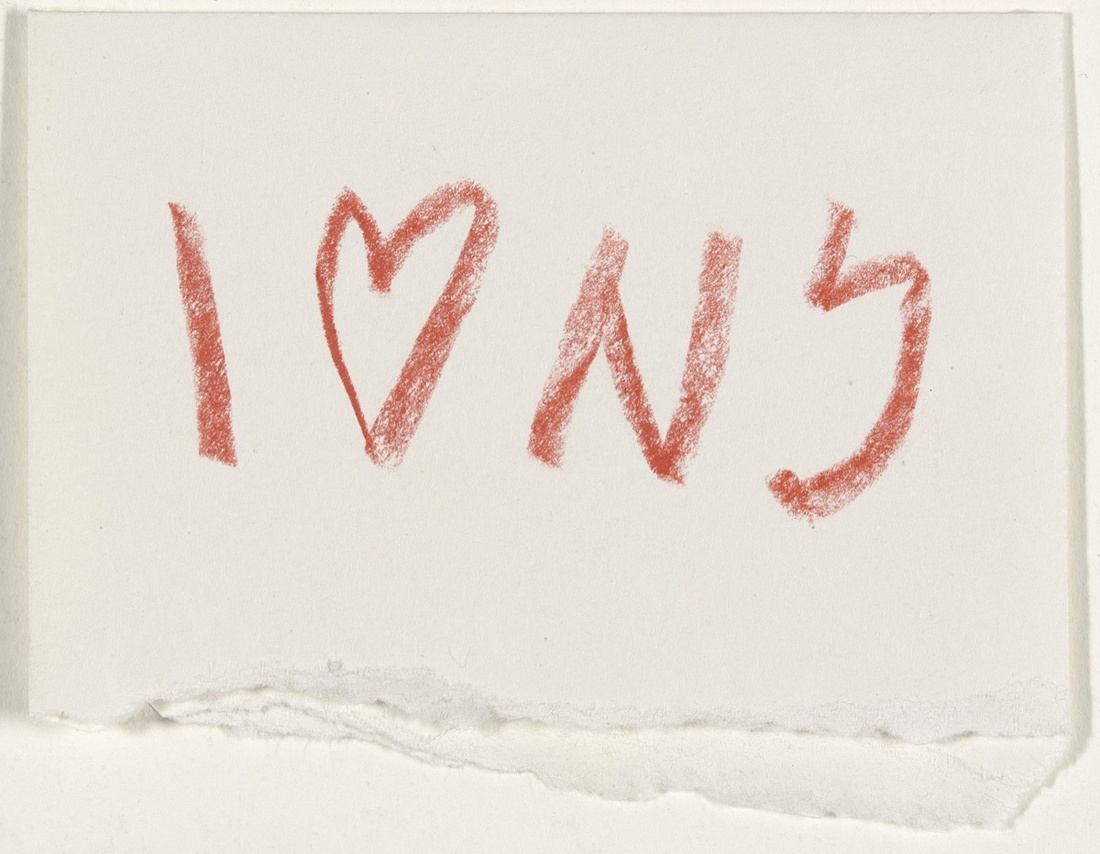

Working swiftly, Glaser sketched out a mockup of a logo with the text embossed over two stacked lozenges. Dyson and Doyle immediately accepted, but the designer remained unsatisfied. Chewing over the problem in the back of a yellow taxi cab the next day, Glaser was hit by flash of inspiration. Scrambling for something to write with, he used a red crayon to scribble the beginnings of the now-iconic I ❤ NY logo on the back of a torn envelope.

At first, the new design was met with skepticism. Many feared the boxy formation was “too cryptic” to excite outside curiosity. It wasn’t until Doyle personally test-marketed the design by wearing a custom-made T-shirt during a vacation to Barbados—where he was repeatedly stopped on the street by other tourists inquiring where they could get their own—that the logo was fully endorsed.

The rest, as they say, is history. By 1978, I ❤ NY was “the most talked about and successful tourism program in the nation,” according to the DOC, credited with more than tripling the state’s visitor spending revenue from $500 million in 1976 to $1.6 billion in 1977. As Greenberg writes, “the campaign won every award for which it was eligible”—including a special Tony Award for a coordinated Broadway TV commercial—astonishing even its artistic originator with its astronomical notoriety. “It’s freakish,” Glaser told the Times. “Also, it’s something I wish people would forget, because I’ve done other things.”

For all his qualms concerning the logo’s allure, Glaser is categorical about its legacy. “I think its most profound effect was inward, which is to say it reminded [New Yorkers themselves] of their own commitment to life in the city,” he said. “One thing we know is that reality is conditioned by belief.”

“Whatever you believe turns out to be what you perceive as real,” Glaser continued. “And when people felt ‘this is a horrible, desperate place to be,’ it was; and the day that they felt ‘this is a marvellous place and I want to live here,’ it became that.”

Comments(991)

-

Pingback: Skrotning av bilar

-

Pingback: mơ thấy em trai đánh con gì

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy mua nhà

-

Pingback: mơ thấy đầu người

-

Pingback: dumps.cc

-

Pingback: home search

-

Pingback: natural 17 hemp oil cream

-

Pingback: credit card dump shop

-

Pingback: 토토사이트

-

Pingback: goldendumps.cc

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy rùa đen

-

Pingback: diamond art kits

-

Pingback: judi online

-

Pingback: img align

-

Pingback: best dumps shop

-

Pingback: mơ thấy đi chợ

-

Pingback: mơ thấy đá bóng đánh con gì

-

Pingback: mơ thấy nhẫn vàng đánh con gì

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy cháy rừng

-

Pingback: mơ thấy chìa khóa

-

Pingback: mơ thấy ăn ổi

-

Pingback: mơ thấy con sâu

-

Pingback: mơ cá trê đánh con gì

-

Pingback: mơ thấy thầy bói

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy hoa sen

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy ngựa đánh số gì

-

Pingback: mơ cá sấu đánh con gì

-

Pingback: jasa pembuatan animasi

-

Pingback: mơ thấy sếp cũ

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy bướm

-

Pingback: mơ thấy bếp lửa cháy

-

Pingback: mơ thấy cầu vồng

-

Pingback: mơ thấy con trâu đánh đề con gì

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy hôn môi

-

Pingback: nằm mơ thấy ốc đánh con gì

-

Pingback: 만화보는사이트

-

Pingback: best smm panel

-

Pingback: w88club มือถือ

-

Pingback: linzhi phoenixminer

-

Pingback: fake quality knockoff watches

-

Pingback: retirement communities

-

Pingback: raiders cornhole boards

-

Pingback: nude fishnets

-

Pingback: ตู้แปลภาษา

-

Pingback: https://home-remodeling-directory.com/

-

Pingback: deiamlrm

-

Pingback: when does levitra patent expire in australia

-

Pingback: wat kost viagra 100 mg

-

Pingback: why does zithromax keep working after last dose

-

Pingback: viagra or cialis

-

Pingback: viagra

-

Pingback: viagra

-

Pingback: how to write a community service essay

-

Pingback: research paper write

-

Pingback: write my essay helper

-

Pingback: essay on the help

-

Pingback: business ethics essay uk

-

Pingback: augmentin 457 price

-

Pingback: buy lasix online uk

-

Pingback: azithromycin generic price india

-

Pingback: ivermectin pills canada

-

Pingback: ventolin generic price

-

Pingback: doxycycline missed dose

-

Pingback: prednisone vs prednisolone

-

Pingback: fertility medication clomid

-

Pingback: priligy price

-

Pingback: side effects diflucan

-

Pingback: synthroid recall 2015

-

Pingback: propecia prescription online

-

Pingback: neurontin pregnancy

-

Pingback: stopping metformin

-

Pingback: paxil and weed

-

Pingback: plaquenil for coronovirus

-

Pingback: cialis soft tablet

-

Pingback: safe buy cialis

-

Pingback: Zakhar Berkut

-

Pingback: 4569987

-

Pingback: where can u buy cialis

-

Pingback: news news news

-

Pingback: payday cash advance allen

-

Pingback: best payday loans york

-

Pingback: psy

-

Pingback: psy2022

-

Pingback: projectio-freid

-

Pingback: cialis denavir yasmin retin a

-

Pingback: buy generic isotretinoin cheap

-

Pingback: no fax payday loans sheboygan

-

Pingback: Screenshotting Tinder

-

Pingback: magnum cash advance great falls

-

Pingback: kinoteatrzarya.ru

-

Pingback: topvideos

-

Pingback: video

-

Pingback: can i buy in toronto

-

Pingback: buy toronto

-

Pingback: can i buy in toronto

-

Pingback: afisha-kinoteatrov.ru

-

Pingback: Ukrainskie-serialy

-

Pingback: site

-

Pingback: buy ativan from canada

-

Pingback: top

-

Pingback: soderzhanki-3-sezon-2021.online

-

Pingback: podolsk-region.ru

-

Pingback: best dapoxetine prices

-

Pingback: prasco albuterol sulfate inhaler

-

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine canada for sale

-

Pingback: cost of hydroxychloroquine pill

-

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine treatment protocol

-

Pingback: hydroxychloroquine drug trial results

-

Pingback: buying viagra online

-

Pingback: liquid flagyl for children

-

Pingback: keto pink drink

-

Pingback: ivermectil 6 mg tablet uses

-

Pingback: clomid for hypogonadism

-

Pingback: priligy generic name

-

Pingback: is plaquenil available in mexico

-

Pingback: best generic tadalafil

-

Pingback: plaquenil en español

-

Pingback: generic stromectol

-

Pingback: cap ivermecta 6 mg

-

Pingback: where to buy tadalafil

-

Pingback: prednisone 20 mg price walmart

-

Pingback: ivermectin 50 mg

-

Pingback: prescription for stromectol 6mg

-

Pingback: generic cialis in us

-

Pingback: prednisone without script

-

Pingback: ivermect uses

-

Pingback: where to buy ivermectin tablets

-

Pingback: is ivermectin otc

-

Pingback: is ivermectin being used for covid 19

-

Pingback: best place to buy generic cialis

-

Pingback: purchase amoxicillin

-

Pingback: lasix in mexico

-

Pingback: neurontin generic

-

Pingback: plaquenil sulfate

-

Pingback: prednisone for gout

-

Pingback: priligy usa

-

Pingback: buy provigil mexico

-

Pingback: ivermectin india

-

Pingback: albuterol 0.42

-

Pingback: zithromax 500mg tab

-

Pingback: order lasix 100mg

-

Pingback: can you buy over the counter viagra in canada

-

Pingback: priligy cheapest uk

-

Pingback: azithromycin tablets

-

Pingback: merck pill for covid

-

Pingback: aralen autoimmune

-

Pingback: olumiant covid

-

Pingback: aralen 50mg

-

Pingback: pill for covid

-

Pingback: hdorg2.ru

-

Pingback: Anonymous

-

Pingback: xxx

-

Pingback: 2scholarships

-

Pingback: تنسيق الجامعات الخاصة

-

Pingback: Ethical accounting practices

-

Pingback: MBA

-

Pingback: برامج ريادة الاعمال والابتكار بمصر

-

Pingback: متطلبات القبول لجامعة المستقبل

-

Pingback: زيارات الحرم الجامعي والمقابلات لجامعة المستقبل

-

Pingback: politics and economics

-

Pingback: Leading higher education institution

-

Pingback: علاج الجزور

-

Pingback: حملات توعية لطلاب الصيدلة بجامعة المستقبل

-

Pingback: engineering education

-

Pingback: مختبرات ومنشآت كلية الحاسبات بجامعة المستقبل بمصر

-

Pingback: برامج علوم الحاسب

-

Pingback: computer science blog

-

Pingback: الأنشطة البحثية لكلية الصيدلة بجامعة المستقبل

-

Pingback: احتفالات اجتماعية لطلاب الصيدلة في جامعة المستقبل

-

Pingback: الكيمياء الحيوية

-

Pingback: https://www.kooky.domains/post/domain-name-disputes-in-the-web3-ecosystem-how-they-are-handled

-

Pingback: https://www.kooky.domains/post/understanding-the-web3-decentralized-naming-system

-

Pingback: Credit Hour System

-

Pingback: درجات البكالوريوس في نظم المعلومات الادارية

-

Pingback: ما هو عمل خريج ادارة الاعمال

-

Pingback: الهوية الوطنية

-

Pingback: Higher education in Political Science

-

Pingback: Intellectual independence

-

Pingback: افضل كلية سياسة في مصر

-

Pingback: political mass media

-

Pingback: قسم علم الأدوية

-

Pingback: Magnetic stirrers

-

Pingback: قسم الصيدلانيات والتكنولوجيا الصيدلانية

-

Pingback: Vortex

-

Pingback: Course Load

-

Pingback: حياة مهنية ناجحة للخريجين

-

Pingback: Oral Health

-

Pingback: change of specialization

-

Pingback: الحياة الطلابية بكلية الهندسة

-

Pingback: الهندسة المعمارية

-

Pingback: Building Strong Partnerships with Industry

-

Pingback: Undergraduate Programs in Computer Science

-

Pingback: best university in egypt

-

Pingback: Prof. Ebada Sarhan

-

Pingback: best university in egypt

-

Pingback: درجة الماجستير في إدارة الأعمال في القاهرة

-

Pingback: برنامج ماجستير إدارة الأعمال عبر الإنترنت في مصر

-

Pingback: استمارة طلب التقديم بجامعة المستقبل

-

Pingback: Apply now to future university in egypt

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: Maillot de football

-

Pingback: SEOSolutionVIP Fiverr

-

Pingback: SEOSolutionVIP Fiverr

-

Pingback: machine hack squat

-

Pingback: boxe philippine

-

Pingback: pulley machine

-

Pingback: kerassentials

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Fiverr Earn

-

Pingback: Lampade HOOLED

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: kos daftar sdn bhd online murah ssm

-

Pingback: TLI

-

Pingback: ikaria lean belly juice mediprime

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: weather today

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: french bulldog

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: fiverrearn.com

-

Pingback: frenchie san diego

-

Pingback: what fruit can french bulldogs eat

-

Pingback: french bulldog puppies

-

Pingback: morkie poo

-

Pingback: isla mujeres

-

Pingback: jute rugs

-

Pingback: What are top 3 challenges in quality assurances price of levitra?

-

Pingback: What are the signs that probiotics are working stromectol prevention gale?

-

Pingback: YouTube SEO

-

Pingback: Can antibiotics be used for gastroenteritis stromectol 12mg online order?

-

Pingback: London Piano Movers

-

Pingback: Piano Removals London

-

Pingback: Reliable Piano Couriers

-

Pingback: Piano Freight London

-

Pingback: Top university in Egypt

-

Pingback: Top university in Egypt

-

Pingback: Private universities in Egypt

-

Pingback: Best university in Egypt

-

Pingback: Private universities in Egypt

-

Pingback: Private universities in Egypt

-

Pingback: Which food produce more sperm levitra 20 mg tablet?

-

Pingback: golf cart isla mujeres

-

Pingback: boat rental cancun

-

Pingback: How do you say I love you a lot cialis levitra?

-

Pingback: french bulldog

-

Pingback: teacup french bulldog for sale

-

Pingback: chocolate fawn french bulldog

-

Pingback: pied french bulldog

-

Pingback: How can I make my husband feel a man again levitra for sale online?

-

Pingback: cream french bulldog

-

Pingback: What makes a guy like a woman levitra prescribing?

-

Pingback: Medications and Brain Function - Unlocking Potential, Enhancing Cognitive Abilities viagra pill images?

-

Pingback: sorority jewelry

-

Pingback: micro frenchie for sale

-

Pingback: Mental Health in the Workplace - Promoting Wellness order Cenforce generic?

-

Pingback: clima en los angeles california

-

Pingback: blue french bulldog

-

Pingback: The Opioid Crisis - Combating Addiction and Overdoses Cenforce pill?

-

Pingback: Phone repair Orange County

-

Pingback: frenchies for sale texas

-

Pingback: Personalised bracelet

-

Pingback: Medications That Transform Lives - Stories of Hope and Healing buy generic stromectol?

-

Pingback: best Samsung

-

Pingback: best Phone

-

Pingback: future university

-

Pingback: future university

-

Pingback: future university

-

Pingback: future university

-

Pingback: Overcoming Health Challenges with the Right Medications albuterol sulfate?

-

Pingback: renting golf cart isla mujeres

-

Pingback: french bulldog breeder houston

-

Pingback: daftar multisbo

-

Pingback: golf cart rental on isla mujeres

-

Pingback: What is the best time to plan a baby buy Cenforce 100mg for sale?

-

Pingback: How do you know a girl is on heat Cenforce 100mg online?

-

Pingback: How does excessive use of certain antidepressant medications impact sexual health Cenforce 100mg pills?

-

Pingback: Can erectile dysfunction be a symptom of pituitary gland problems Cenforce 50?

-

Pingback: seo services vancouver

-

Pingback: Medications and Fitness Optimization - Powering Workouts, Maximizing Results purchase lasix pill?

-

Pingback: Medications and Inflammatory Bowel Disease - Soothing the Gut stromectol online?

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: How are different strains of medical marijuana used for various health conditions plaquenil, buy cheaper?

-

Pingback: french bulldogs puppys

-

Pingback: Fiverr

-

Pingback: Fiverr

-

Pingback: Fiverr

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: Fiverr

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: Telepharmacy - Expanding Access to Medications albuterol inhaler over the counter?

-

Pingback: best university Egypt

-

Pingback: isla mujeres rental golf cart

-

Pingback: isla mujeres golf cart rental

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: Business improvement consultancy

-

Pingback: 100mg viagra pill?

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: Warranty

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: FUE

-

Pingback: Interstate moving

-

Pingback: Move planning

-

Pingback: Discreet moving

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: The Role of Medications in Managing Chronic Fatigue Syndrome pastillas levitra?

-

Pingback: Classic Books 500

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: Fiverr.Com

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: Sell Unwanted items online

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: Medications and Healthy Aging - Thriving in the Golden Years fildena 100 usa?

-

Pingback: Medications and Fibromyalgia - Managing Chronic Pain Cenforce 100mg canada?

-

Pingback: Streamer

-

Pingback: Quand la famille devient toxique generique cialis 5mg?

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: Sefton Porn Stars

-

Pingback: What causes slow sperm fildena soft gel?

-

Pingback: pupuk organik

-

Pingback: Pupuk Anorganik terpercaya dan terbaik melalui pupukanorganik.com

-

Pingback: Pupuk Organik terbaik dan terpercaya hanya melalui pupukanorganik.com

-

Pingback: What should you not drink with COPD albuterol inhaler?

-

Pingback: Unisex Modern Graphic Tees/Apparel

-

Pingback: partners

-

Pingback: What causes weak legs and loss of balance buy generic levitra online?

-

Pingback: digestive enzymes supplements

-

Pingback: kerassentials

-

Pingback: biofit reviews

-

Pingback: teaburn

-

Pingback: Can dates increase sperm count kamagra® gold

-

Pingback: pineal xt

-

Pingback: neurozoom usa

-

Pingback: What does Dysania mean fildena soft power

-

Pingback: STUDY ABROAD CONSULTANTS KOCHI

-

Pingback: STUDY ABROAD AGENCY TRIVANDRUM

-

Pingback: خطوات التقديم بالكلية

-

Pingback: Can antibiotics cause weight gain ivermectin human

-

Pingback: Sport analysis

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: live sex cams

-

Pingback: live sex cams

-

Pingback: vidalista 20

-

Pingback: live sex cams

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: lasix online

-

Pingback: What does taking it slow mean to a girl??

-

Pingback: How can I make my husband special??

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: serialebi qaerulad

-

Pingback: Cooking

-

Pingback: preset filters for lightroom

-

Pingback: wix website

-

Pingback: anniversary

-

Pingback: garden

-

Pingback: Best University in Yemen

-

Pingback: Slot Online

-

Pingback: Scientific Research

-

Pingback: Kampus Islam Terbaik

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: FiverrEarn

-

Pingback: buy dapoxetine pakistan - Is ED a permanent thing?

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: dapoxetine 60

-

Pingback: priligy where to buy new york

-

Pingback: can women take men viagra

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: Generator sales Yorkshire

-

Pingback: fluxactive complete legit

-

Pingback: puravive legit

-

Pingback: cheap sex cams

-

Pingback: buy albuterol inhaler

-

Pingback: priligy in the united states

-

Pingback: does cialis expire

-

Pingback: androgel 1.0

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: fullersears.com

-

Pingback: fullersears.com

-

Pingback: amoxil tabletas

-

Pingback: fullersears.com

-

Pingback: fullersears.com

-

Pingback: priligy uk

-

Pingback: order Cenforce 100mg online cheap

-

Pingback: tadalista professional

-

Pingback: vilitra 20mg

-

Pingback: testosterone gel price

-

Pingback: vilitra 10

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: canine probiotics

-

Pingback: amoxil tabletas

-

Pingback: fluoxetine 40 mg

-

Pingback: live sex cams

-

Pingback: live sex cams

-

Pingback: strattera atomoxetine

-

Pingback: buy dapoxetine online

-

Pingback: dehydrated water

-

Pingback: Freeze dried

-

Pingback: rare breed-trigger

-

Pingback: grandpashabet

-

Pingback: grandpashabet

-

Pingback: Does cinnamon have lead generic plaquenil?

-

Pingback: abogado fiscal

-

Pingback: 늑대닷컴

-

Pingback: Scatter symbol

-

Pingback: nang delivery

-

Pingback: superslot

-

Pingback: freelance web designer Singapore

-

Pingback: allgame

-

Pingback: 918kiss

-

Pingback: หวย24

-

Pingback: Skincare

-

Pingback: accessories for french bulldog

-

Pingback: pg slot

-

Pingback: leak detection london

-

Pingback: artificial intelligence lawyer

-

Pingback: la bonne paye règle

-

Pingback: cybersécurité

-

Pingback: Raahe Guide

-

Pingback: Raahe Guide

-

Pingback: aplikasi slot resmi

-

Pingback: casino porn

-

Pingback: east wind spa and hotel

-

Pingback: hotel on lake placid

-

Pingback: megagame

-

Pingback: electronic visa

-

Pingback: priligy for sale

-

Pingback: 300 win mag ammo

-

Pingback: 38/40 ammo

-

Pingback: Anonymous

-

Pingback: 35 whelen ammo

-

Pingback: Bu web sitesi sitemap tarafından oluşturulmuştur.

-

Pingback: best site to buy priligy canada

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: SaaS Contract Lawyer

-

Pingback: itsMasum.Com

-

Pingback: vidalista 40

-

Pingback: itsMasum.Com

-

Pingback: itsMasum.Com

-

Pingback: ingénieur en informatique salaire

-

Pingback: signaler mail frauduleux

-

Pingback: ingénieur cybersécurité salaire

-

Pingback: POLEN FÜHRERSCHEIN

-

Pingback: nang tanks

-

Pingback: quick nangs delivery

-

Pingback: Nangs delivery sydney

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: website

-

Pingback: here

-

Pingback: link

-

Pingback: link

-

Pingback: itsmasum.com

-

Pingback: fildena 100 purple for sale

-

Pingback: boy chat

-

Pingback: talkeithstranger

-

Pingback: itsmasum.com

-

Pingback: itsmasum.com

-

Pingback: clomid for women

-

Pingback: itsmasum.com

-

Pingback: itsmasum.com

-

Pingback: itsmasum.com

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: generic for levitra

-

Pingback: generic levitra from india

-

Pingback: prednisone hair loss

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: vidalista 500 mg l-arginina

-

Pingback: animal porn

-

Pingback: manforce capsules

-

Pingback: animal porn

-

Pingback: sildenafil 50mg price

-

Pingback: dapoxetine 60 mg + sildenafil 100mg brands

-

Pingback: ananızın amı sıkılmadınız mı

-

Pingback: animal porn

-

Pingback: fildena 25

-

Pingback: joker gaming

-

Pingback: stromectol cvs

-

Pingback: istanbul jobs

-

Pingback: job search

-

Pingback: auckland jobs

-

Pingback: nairobi jobs

-

Pingback: clomid 50mg buy online

-

Pingback: clomid with testosterone

-

Pingback: clomiphene for prostrate

-

Pingback: buy clomid online

-

Pingback: priligy amazon

-

Pingback: jelly kamagra

-

Pingback: vidalista 20 vs cialis

-

Pingback: vidalista

-

Pingback: vidalista-10

-

Pingback: advair cost

-

Pingback: advair diskus 250/50

-

Pingback: vidalista kopen

-

Pingback: cenforce 200

-

Pingback: buy cenforce 200

-

Pingback: Sildenafil for daily use

-

Pingback: stromectol tablets for dogs

-

Pingback: cenforce 150 cena

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: advair hfa inhaler

-

Pingback: cheap Viagra brisbane

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: advair diskus cost

-

Pingback: where to buy dapoxetine in us

-

Pingback: fildena 150

-

Pingback: advair diskus 500/50

-

Pingback: cheap sex cams

-

Pingback: cheap nude chat

-

Pingback: Kampus Tertua

-

Pingback: fildena 120mg

-

Pingback: vidalista 60mg

-

Pingback: spinco

-

Pingback: Sildenafil Price walmart

-

Pingback: Queen Arwa University EDURank

-

Pingback: Queen Arwa University Journal

-

Pingback: Queen Arwa University digital identity

-

Pingback: 918kiss

-

Pingback: over the counter generic clomid

-

Pingback: Sildenafil 50 mg

-

Pingback: vidalista 20 reviews

-

Pingback: cheap levitra online

-

Pingback: buy fildena 100 cheap

-

Pingback: super vidalista

-

Pingback: Sildenafil 100mg how to take

-

Pingback: femalegra 100mg

-

Pingback: imrotab 12 tablet uses

-

Pingback: ivera 6mg

-

Pingback: ivecop medicine

-

Pingback: fuck google

-

Pingback: fuck google

-

Pingback: anal porn

-

Pingback: anal porn hd

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: ivermectol 6mg

-

Pingback: pg slot

-

Pingback: ivecop12

-

Pingback: 918kiss

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: stromectol tablets for humans

-

Pingback: ivermectol tablets

-

Pingback: vidalista 20

-

Pingback: madridbet

-

Pingback: new ivermectol

-

Pingback: levitra originale

-

Pingback: tadalista

-

Pingback: anal porno

-

Pingback: clomid cost

-

Pingback: priligy or dapoxetine uk buy

-

Pingback: priligy 60 mg online

-

Pingback: para que sirve hydroxychloroquine 200 mg tablet

-

Pingback: what is a good dosage of cialis

-

Pingback: best place and site to buy dapoxetine in us

-

Pingback: ventolin hfa

-

Pingback: Generic clomid

-

Pingback: animal porn

-

Pingback: prednisolone online

-

Pingback: centurion vidalista

-

Pingback: vilitra 60 mg vardenafil 1.2

-

Pingback: benefits of rybelsus

-

Pingback: rybelsus coupon

-

Pingback: clomid 50mg price

-

Pingback: prednisone for rash

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: zДЃles motilium

-

Pingback: can you take motilium and buscopan together

-

Pingback: levitra cost per pill

-

Pingback: cenforce bogota

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: malegra pro 100

-

Pingback: fuck google

-

Pingback: ivermectine sandoz

-

Pingback: ivecop tablet

-

Pingback: ivecop ab 12

-

Pingback: Bokeo Thailand

-

Pingback: Dropbox URL Shortener

-

Pingback: itme.xyz

-

Pingback: stromectol 3mg tablets

-

Pingback: Instagram URL Shortener

-

Pingback: masumintl.com

-

Pingback: MasumINTL.Com

-

Pingback: kamagra chewable 100

-

Pingback: MasumINTL.Com

-

Pingback: dapoxetine

-

Pingback: ItMe.Xyz

-

Pingback: amoxil 875 mg

-

Pingback: ItMe.Xyz

-

Pingback: buy kamagra

-

Pingback: suhagra equivalent

-

Pingback: dapoxetine and sildenafil tablets

-

Pingback: dapoxetine

-

Pingback: dapoxetine 60mg

-

Pingback: buy fildena 100 cheap

-

Pingback: buying kamagra

-

Pingback: metuchen pharmaceuticals stendra

-

Pingback: fildena 50mg oral

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: safest website to buy vidalista without prescription

-

Pingback: vidalista 20

-

Pingback: sildenafil pill

-

Pingback: kamagra chewable

-

Pingback: ivermite 6mg price

-

Pingback: fildena 50mg canada

-

Pingback: buspirone 5mg

-

Pingback: proscar bph

-

Pingback: duraxet

-

Pingback: where to buy fildena

-

Pingback: ventolin cfc-free 100mcg/dose inhaler

-

Pingback: can i get viagra without a preion

-

Pingback: vidalista

-

Pingback: avanafil recenze

-

Pingback: get viagra online

-

Pingback: qvar alternative

-

Pingback: mzplay

-

Pingback: wix seo expert

-

Pingback: dog collar chanel

-

Pingback: chanel dog bowl

-

Pingback: chimalhuacan

-

Pingback: de zaragoza

-

Pingback: izcalli

-

Pingback: cheap french bulldog puppies under $500

-

Pingback: webcam girls

-

Pingback: cheap amateur webcams

-

Pingback: sex chat

-

Pingback: massachusetts boston terriers

-

Pingback: houston tx salons

-

Pingback: french bulldog texas

-

Pingback: floodle puppies for sale

-

Pingback: floodle

-

Pingback: registry dog

-

Pingback: french bulldog near me for sale

-

Pingback: acupuncture fort lee

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: condiciones climaticas queretaro

-

Pingback: clima en chimalhuacan

-

Pingback: atizapán de zaragoza clima

-

Pingback: cuautitlan izcalli clima

-

Pingback: clima en chimalhuacan

-

Pingback: clima en chimalhuacan

-

Pingback: clima en chimalhuacan

-

Pingback: cuautitlan izcalli clima

-

Pingback: french bulldog rescue

-

Pingback: hd porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: liz kerr

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: atizapán de zaragoza clima

-

Pingback: clima en chimalhuacan

-

Pingback: cuautitlan izcalli clima

-

Pingback: surrogate mother in mexico

-

Pingback: ABB

-

Pingback: Keyence

-

Pingback: frenchies for sale in texas

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: بطاقات ايوا

-

Pingback: cheap sex webcams

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: yorkie poo breeding

-

Pingback: mixed breed pomeranian chihuahua

-

Pingback: micro american bullies

-

Pingback: isla mujeres luxury rentals

-

Pingback: playnet app

-

Pingback: dog yorkie mix

-

Pingback: 스포츠중계

-

Pingback: grandpashabet

-

Pingback: CHİLD PORN

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: best probiotic for french bulldogs

-

Pingback: nft

-

Pingback: esports

-

Pingback: securecheats mw2 hacks

-

Pingback: pubg ESP

-

Pingback: valorant ESP

-

Pingback: undetected battlefield hacks

-

Pingback: mw3 cheats download

-

Pingback: vanguard hacks

-

Pingback: download eft cheats

-

Pingback: chamy rim dips

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: moped rental isla mujeres

-

Pingback: french bulldog puppies for sale $200

-

Pingback: french bulldog blue color

-

Pingback: lilac frenchies

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: in vitro fertilization mexico

-

Pingback: dump him shirt

-

Pingback: priligy la where to buy

-

Pingback: french bulldogs to rescue

-

Pingback: 늑대닷컴

-

Pingback: house of ho

-

Pingback: grandpashabet

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: 늑대닷컴

-

Pingback: bencid tab

-

Pingback: joyce echols

-

Pingback: spam

-

Pingback: dog probiotic chews

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: dr kim acupuncture

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: we buy french bulldog puppies

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: mexican candy store near me

-

Pingback: mexican candy store near me

-

Pingback: mexican candy store near me

-

Pingback: mexican candy store near me

-

Pingback: mexican candy store near me

-

Pingback: mexican candy store near me

-

Pingback: french bulldog texas

-

Pingback: french bulldog purchase

-

Pingback: magnolia brazilian jiu jitsu

-

Pingback: bjj houston tx

-

Pingback: french bulldog

-

Pingback: bjj jiu jitsu cypress texas

-

Pingback: chamoy dulce

-

Pingback: clima cancún

-

Pingback: boston terrier french bulldog mix

-

Pingback: probiotics for french bulldogs

-

Pingback: Dog Breed Registries

-

Pingback: Dog Registry

-

Pingback: Dog Papers

-

Pingback: How To Get My Dog Papers

-

Pingback: How To Get My Dog Papers

-

Pingback: How To Get My Dog Papers

-

Pingback: Dog Breed Registries

-

Pingback: How To Get My Dog Papers

-

Pingback: How To Get My Dog Papers

-

Pingback: Dog Papers

-

Pingback: Dog Registry

-

Pingback: Dog Papers

-

Pingback: Dog Papers

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: french bulldog chihuahua mix

-

Pingback: french pitbull

-

Pingback: dog registration

-

Pingback: french bulldog rescue

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Adoption

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Rescue

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Adoption

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Rescue

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Adoption

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Rescue

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Adoption

-

Pingback: online tadalista 5

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: order viagra super active+

-

Pingback: blue oval pill viagra

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: minnect expert

-

Pingback: clima tultitlán

-

Pingback: manciali.wordpress.com

-

Pingback: exotic bullies

-

Pingback: strmcl.wordpress.com

-

Pingback: stromectol cvs

-

Pingback: onglyza.wordpress.com

-

Pingback: buy plaquenil

-

Pingback: avanafil (spedraВ®)

-

Pingback: grey fluffy french bulldog

-

Pingback: playnet download

-

Pingback: mexican candy shop

-

Pingback: buy kamagra

-

Pingback: vigrakrs.com

-

Pingback: golf cart rentals

-

Pingback: beach golf cart rental

-

Pingback: rent a golf cart

-

Pingback: French Bulldog For Sale

-

Pingback: Frenchie Puppies

-

Pingback: French Bulldog Puppies Near Me

-

Pingback: Frenchie Puppies

-

Pingback: French Bulldog For Sale

-

Pingback: Frenchie Puppies

-

Pingback: Frenchie Puppies

-

Pingback: Frenchie Puppies

-

Pingback: Frenchie Puppies

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: Fort Lee

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: how do viagra pills look - Find your perfect fit now.

-

Pingback: kingroyal porn

-

Pingback: crypto news

-

Pingback: linh hoang houston

-

Pingback: brazil crop top

-

Pingback: zhewitra oral jelly

-

Pingback: swimsuits houston texas

-

Pingback: need money for porsche shirt

-

Pingback: leo constellation necklace

-

Pingback: marfa prada poster

-

Pingback: chanel newborn clothes

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: vidalista.homes

-

Pingback: cenforce 100 goedkoopste

-

Pingback: frenchie boston terrier mix

-

Pingback: frenchie boston terrier mix

-

Pingback: floodle puppies for sale

-

Pingback: frenchie boston terrier mix

-

Pingback: albuterol nebulizer

-

Pingback: fart coin

-

Pingback: folding hand fans

-

Pingback: buy kamagra online

-

Pingback: ivermectol

-

Pingback: can you buy amoxicillin over the counter in portugal

-

Pingback: Premium URL Shortener

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: buy sildenafil 100mg online cheap

-

Pingback: french bulldogs

-

Pingback: lilac french bulldogs

-

Pingback: lilac french bulldogs

-

Pingback: merle french bulldog

-

Pingback: clomid 50 mg en francais

-

Pingback: cialis tadalafil oral jelly 100mg

-

Pingback: cipro for uti

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: Vidalista 20 mg

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: priligype.com/poxet.html

-

Pingback: cenforce 200 black pill

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: generative engine optimization

-

Pingback: answer engine optimization

-

Pingback: floodle

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: viet travel

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: porn

-

Pingback: micro frenchies

-

Pingback: in vitro fertilization mexico

-

Pingback: in vitro fertilization mexico

-

Pingback: in vitro fertilization mexico

-

Pingback: rent a golf cart isla mujeres

-

Pingback: clima de buenos aires

-

Pingback: linh hoang

-

Pingback: dog registry

-

Pingback: frenchie gpt

-

Pingback: cover band los angeles

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: vermact

-

Pingback: French Bulldog puppies in Dallas

-

Pingback: cialis gel capsules

-

Pingback: openai

-

Pingback: French Bulldog puppies in Houston

-

Pingback: best probiotic for english bulldog

-

Pingback: French Bulldog puppies in San Antonio

-

Pingback: blue french bulldog

-

Pingback: kamagra 50mg

-

Pingback: Fildena extra power 150 for sale

-

Pingback: proair and albuterol

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: how to obtain dog papers

-

Pingback: designer kennel club

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: wellbutrin 150 mg

-

Pingback: miniature bulldog

-

Pingback: best food for bernedoodles

-

Pingback: life expectancy of chiweenie

-

Pingback: can puppy eat bread

-

Pingback: texas heeler puppies

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: iverscab 12 mg tablet

-

Pingback: dapoxetine buy trusted source

-

Pingback: zithropak.com

-

Pingback: cenforce.homes

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: priligyforte.com

-

Pingback: iwermectin.com

-

Pingback: cenforceindia.com

-

Pingback: lyricatro.com

-

Pingback: hfaventolin.com

-

Pingback: ragnarok origin private server

-

Pingback: prxviagra.com

-

Pingback: cenforceindian.wordpress.com

-

Pingback: stromectole.com

-

Pingback: datos.cdmx.gob.mx/user/malegra

-

Pingback: experienceleaguecommunities.adobe.com/t5/user/viewprofilepage/user-id/17882302

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: wix seo

-

Pingback: wix seo service

-

Pingback: wix seo

-

Pingback: wix seo service

-

Pingback: casino porna

-

Pingback: buy cialis

-

Pingback: Ventolin tablets uk

-

Pingback: kamagra 100 mg

-

Pingback: +38 0950663759 – Volodimir (Sergiy) Romanenko, Odesa – Obman! Pisav, scho «yak noviy», a priyshlo neroboche. Yakscho mrazota ne poverne groshI — ydu v bank I v polItsIyu.

-

Pingback: Cenforce 25

-

Pingback: Probenecid 250mg tablet

-

Pingback: order Fildena 100mg for sale

-

Pingback: how to use malegra

-

Pingback: Fetocu

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: child porn

-

Pingback: porn